The function of a state of law by creating strong modern institutions was one of the fundamental values in which Eleftherios Venizelos believed. He had the talent of imposing his views by the power of his arguments within institutional limits. However, he did not hesitate, to resort to dynamic actions or revolutionary confrontation against the state when he felt that the national interests were at stake, whether in Crete or in Greece.

His first actual participation in revolutionary armed confrontation took place during the Cretan Revolution in 1897, which was when his diplomatic virtues became apparent and he gradually emerged as its leader.

In 1898 Crete was liberated from the Turks and the Great Powers decided to grant autonomy to the island, which was under their protection and under the Sultans’ rule. Autonomy was concerned only with the exercise of internal policy and not with foreign affairs decisions.

Thus begins the period of the Autonomous Cretan State. Prince George (son of King George I of Greece) was appointed as The High Commissioner of Crete. The Prince was received with great enthusiasm upon his arrival at the port of Souda on December 9, 1898. Eleftherios Venizelos was a member of the Committee for the first Constitution of the State and in 1899, in the government of the prince, he was appointed as a minister of justice.

Initially the two men cooperated smoothly. Soon, however, Venizelos and the Prince had a major disagreement over the handling of the Cretan Question and the authoritarian way of governing by the prince, which was in opposition to Venizelos’ liberal beliefs. For this reason, Venizelos had resigned twice, but his resignations were not accepted. In 1901 the prince ousted Venizelos from the government.

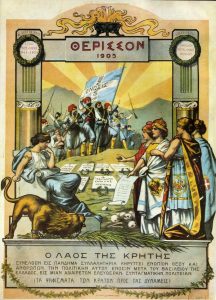

The definitive rupture in their relations led Venizelos to organize an armed movement in Therisso in March 1905, along with his close associates Constantine Foumis and Constantine Manos. They immediately proclaimed Crete’s union with Greece, without being crushed by the Prince’s threatening actions and the wave of terrorism he launched against them.

In Therisso they printed the Official Newspaper of the Revolutionary Assembly, stamps and the newspaper Therisso. Meanwhile, the Great Powers disagreed over whether or not to suppress the revolution, which gradually spread throughout the island. The bloodiest clashes between Russians and the revolutionaries took place in Atsipopoulo and Georgioupoli.

Throughout the revolution, Venizelos was engaged in an intense diplomatic activity and held tough negotiations with the representatives of the Great Powers. Eight months after it started, due to the lack of financial resources for its maintenance and the danger that the Powers would intervene militarily, the revolution ended with a fair compromise. Venizelos himself in Mournies announced its end to the consuls of the Great Powers.

The revolution had positive results, because although the Union was not achieved, Prince George was forced to resign and leave Crete. In 1906 a new High Commissioner was appointed, the liberal politician Alexander Zaimis, and the Cretan Parliament drafted a new, democratic constitution that guaranteed civil and political rights.

Thus, after the revolution of Therisso, a new liberal period began for the island, which essentially paved the way for its subsequent union with Greece. For Eleftherios Venizelos the revolution justified his choices and made him an important political figure with pan-Hellenic and international recognition.