28 Jun The revolutionary

The function of a state of law by creating strong modern institutions was one of the fundamental values in which Venizelos believed. He had the talent of imposing his views by the power of his arguments within institutional limits. He did not hesitate, however, when he felt the national interests were at stake, to resort to dynamic actions, to a revolutionary confrontation with the state, whether in Crete or in Greece. And whenever he took such a decision, he always set a feasible target and persisted in accomplishing it without compromise until he obtained the result that would justify his decision, no matter how painful the consequences might be.

The function of a state of law by creating strong modern institutions was one of the fundamental values in which Venizelos believed. He had the talent of imposing his views by the power of his arguments within institutional limits. He did not hesitate, however, when he felt the national interests were at stake, to resort to dynamic actions, to a revolutionary confrontation with the state, whether in Crete or in Greece. And whenever he took such a decision, he always set a feasible target and persisted in accomplishing it without compromise until he obtained the result that would justify his decision, no matter how painful the consequences might be.

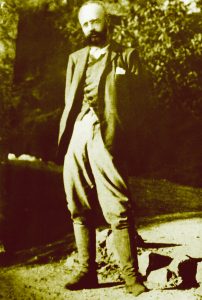

His first actual participation in a revolutionary armed confrontation with Cretan authorities took place during the Cretan revolution in 1897. This revolution, the last in a series of bloody rebellions against the Ottoman rule throughout the 19th century, aimed at achieving the union of Crete with Greece.

The events that broke out in early 1897 (massacres and settings the town of Hania on fire, similar incidents in Rethymnon and Heraklion) led Eleftherios Venizelos, along with other revolutionaries, to Akrotiri near Hania. The resulting clash between the latter and the Turkish forces compelled the Great Powers to intervene in the conflict and to bombard the revolutionary camp at Akrotiri. During the revolution, the diplomatic virtues of Eleftherios Venizelos became apparent and he gradually emerged as its leader. This revolution and the intervention of the Great Powers ended in the establishment of an autonomous regime in Crete.

In the new regime of the island, “the Cretan State”, which was established in Crete in 1898 under Prince George, the son of George I, the king of Greece, Eleftherios Venizelos was appointed Chancellor of Justice. Eleftherios Venizelos’s liberal principles and his disagreement with Prince George on issues related to the future international status of the island led him to a confrontation with the totalitarian Prince, who dismissed him in March 1901. Having been deprived of an alternative institutional means to express his opposing views, in March 1905, Venizelos resorted to an uprising at Therisso, a small village in an inaccessible area in West Crete. His attitude and the international interest he drew to his person led the Protecting Powers to replace Prince George with a new High Commissioner, the distinguished Greek politician Alexamder Zaimis. The new regime adopted a new liberal constitution, and, through more adventures, led the island to its unification with Greece.

Ten years later, in 1915, as a Prime Minister of Greece during the crucial years of World War I, Venizelos clashed with King Constantine over crucial choices of Greek foreign policy and over the role of the throne in the framework of the institutions. Venizelos argued that Greece should enter the war on the side of the Entente and secure the best possible terms for joining that camp. King Constantine, bound by family ties with the German Emperor Wilhelm II and under the influence of his General Staff, insisted on maintaining an ambivalent neutrality during the war. This dispute developed into a major conflict between the Liberal Party and the traditional old parties supporting King Constantine. This conflict was not resolved even by resort to general elections, since, despite Venizelos’s victory, Constantine persisted in his policy. In September 1915, Venizelos resigned from office. One year later, when he saw that the policy of the royalist governments was leading the country to disaster, he left for Thessaloniki, where he set up a Provisional Government and declared the participation of Greece in the war on the side of the Entente. Now Greece had two governments with two diametrically opposite policies. The authority of the Provisional Government extended over Northern Greece up to the valley of Tembi, including Crete and the islands of Eastern Aegean and was maintained thanks to the military support of the Anglo-French expeditionary force stationed in Thessaloniki and to the financial assistance of the Allies. In June 1917, with the aid of French and British forces Venizelos compelled Constantine to abdicate and, in July 1917, the reunited country entered the war on the Entente’s side, taking part in the last military operations of the Macedonian front in the summer and autumn of 1918. The eventual prevalence of the Entente forces and the participation of Greece in the final settlement on the winners’ side vindicated Venizelos’s policy.

During the initial inter-war years, Venizelos, who lived in self-exile in Paris, avoided direct interference in Greek domestic affairs and in the military coups that took place. During that period, the old Liberal Party officials, who had distinguished themselves as his associates during the first creative decade (Kafandaris, Michalakopoulos, Papanastasiou) withdrew gradually from the Party. In an era of increasing economic crisis and class conflicts, when political confrontation was inflamed by continuous reference to the passions of the past, Venizelos no longer benefited from the advice of experienced men in his close environment. The issue concerning the country’s regime, the attempted coup of Plastiras on March 5, 1933the assassination attempt against Venizelos in June of the same year, the widespread and increasing fear of an overthrow of the regime by uncontrolled political forces had created conditions of political instability both in Greece and the rest of Europe. Throughout this period, Venizelos, although trapped in a vicious circle of political polarisation, had not chosen to destabilise the regime. On the contrary, during the last period of his premiership in Greece (1928-1932), he tried to stabilise the republican regime and to bridge the gap that divided the nation. His efforts failed, possibly due to miscalculated political decisions. Within this context, in March 1935, a handful of Venizelist navy officers organised a coup during which they persuaded Venizelos, who had already been out of politics since 1933 and was living a private life in Hania, to come out in support. The coup was unsuccessful and Venizelos, along with his wife and some of his collaborators, took the road to self-exile via the Dodecanese Islands and Rome, finally arriving in Paris. Although in an attempt at reconciliation, King George II, who had returned to Greece, and his government, had granted an amnesty to Venizelos and certain leaders of the coup, Venizelos did not return to Greece because his death intervened in March 1936.